Can simply asking each other a set of specific questions really make two people fall in love?

That’s the idea behind the famous “36 Questions That Lead to Love.” This concept became widely known after a viral essay, but it’s actually based on real psychological research about how people build deep emotional connections.

Today, these 36 questions are being used in all kinds of situations. Some people bring them along on first dates to create a meaningful bond quickly. Others, including marriage counselors, recommend them to couples who want to reconnect and strengthen their relationship. The idea is simple: the more we open up to someone, the closer we feel to them.

Here’s how the 36 questions work and the science behind them.

What are the 36 questions to fall in love?

The so-called 36 questions to fall in love are a set of questions developed in the 1990s by psychologists Arthur Aron, Ph.D., Elaine Aron, Ph.D., and other researchers to see if two strangers can develop an intimate connection just from asking each other a series of increasingly personal questions.

Arthur Aron, a prominent social psychologist, has made significant contributions to understanding human relationships and intimacy. His groundbreaking research on interpersonal closeness led to the development of a set of questions that can foster intimacy and potentially make people fall in love.

Arthur Aron began his academic journey with a deep interest in human connections and what makes relationships thrive. He stumbled upon the idea of using structured questions to create intimacy while investigating the dynamics of interpersonal closeness. His curiosity about how people form bonds led him to experiment with ways to facilitate deep connections quickly and meaningfully.

The philosophy behind Aron’s research lies in the belief that vulnerability and self-disclosure are fundamental to building intimate relationships. The idea is that when two individuals share personal thoughts, feelings, and experiences, they create a sense of closeness and understanding. This is rooted in the broader psychological principle that sharing emotions and thoughts can lead to increased empathy and trust.

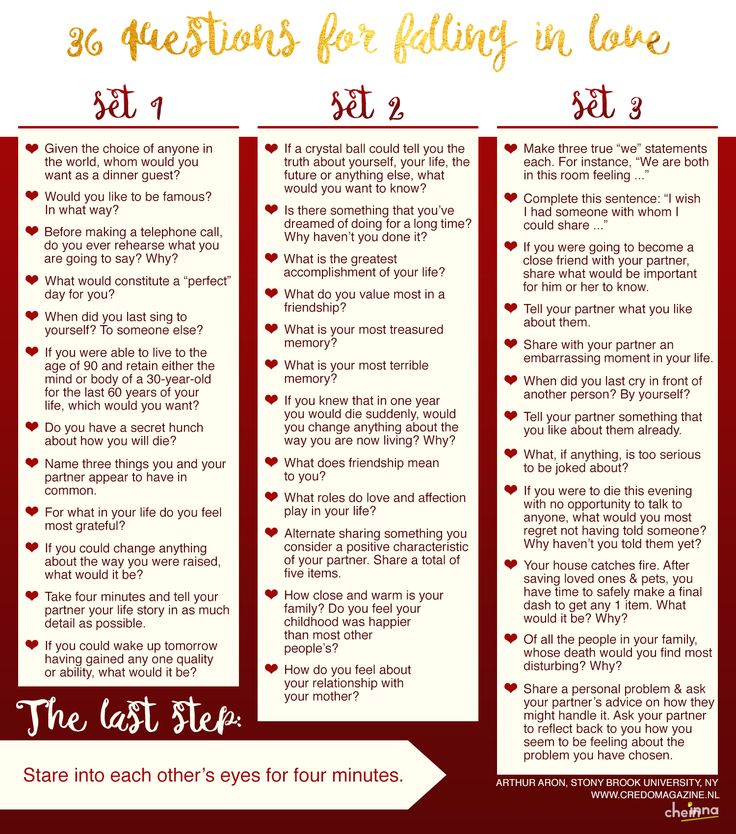

In a seminal study conducted in 1997, Aron and his colleagues designed an experiment to test the hypothesis that mutual vulnerability fosters closeness. They created a set of 36 questions, divided into three sets of increasing intimacy, that pairs of participants would ask each other. The questions are designed to encourage gradual self-disclosure, starting with less personal topics and moving toward more profound and meaningful subjects.

The 36 Questions to fall in Love

Mandy Len Catron’s essay “To Fall in Love with Anyone, Do This,” published in the New York Times’ Modern Love column in 2015, brought Arthur Aron’s experiment into the spotlight. The essay detailed Catron’s personal experience using Aron’s 36 questions, originally developed as a scientific experiment to foster intimacy between strangers. Her narrative explored the profound impact of these questions on forming connections and offered a contemporary reflection on love and vulnerability.

Arthur Aron’s experiment, initially conducted in the early 1990s, aimed to explore the dynamics of interpersonal closeness. Participants were paired up and asked to answer a series of 36 questions, each designed to gradually increase in intimacy. The idea was that by sharing personal thoughts, feelings, and experiences, individuals could foster a sense of closeness and understanding that might otherwise take much longer to develop naturally.

The questions are divided into three sets, each more intimate than the last. They begin with relatively innocuous topics, such as “Would you like to be famous? In what way?” and progress to deeper, more personal inquiries like “What is your most treasured memory?” and “When did you last cry in front of another person?”

The experiment was based on the hypothesis that mutual vulnerability fosters closeness. By gradually opening up to one another, participants could build a foundation of trust and empathy, potentially leading to feelings of intimacy and affection.

Catron’s Experience

Mandy Len Catron’s essay recounts her decision to try the experiment with a casual acquaintance. She was intrigued by the possibility that two people could cultivate love intentionally through a structured process. Catron and her partner, whom she referred to as “the man,” agreed to go through the 36 questions during an evening together. As they progressed through the questions, Catron noted a shift in the nature of their conversation. Initially, the questions sparked curiosity and interest, but as they moved to more personal topics, the vulnerability and intimacy deepened. Catron described feeling a sense of closeness and connection that surprised her, even though she and her partner had not known each other well before the experiment.

One particularly memorable moment came when they reached the final task: staring into each other’s eyes for four minutes without speaking. Catron reflected on how challenging and powerful this experience was, as it required a level of presence and openness that was both uncomfortable and transformative. The exercise forced them to confront their feelings and vulnerabilities, creating an emotional bond that transcended words.

The Essay’s Impact

Catron’s essay quickly gained popularity, resonating with readers who were fascinated by the idea that love could be intentionally cultivated through a structured process. Her story captured the imagination of those who wondered if such an approach could work for them and sparked widespread interest in Arthur Aron’s experiment. The feedback Catron received highlighted a range of reactions from readers. Some were inspired by her story and eager to try the experiment themselves, hopeful that it might help them forge deeper connections in their own lives. Others expressed skepticism, questioning whether true love could be engineered through a series of questions. In her essay, Catron acknowledged these doubts but emphasized that the experiment was not necessarily a guarantee of love. Instead, she argued, it was an opportunity to create the conditions for intimacy and vulnerability, which are essential components of any meaningful relationship. Catron also addressed the criticism that the experiment might trivialize the complexity of love. She pointed out that the questions were not a magic formula for romance but rather a tool for fostering understanding and connection. The real challenge, she suggested, lay in maintaining the openness and vulnerability that the questions encouraged beyond the initial encounter.

Set I

- Given the choice of anyone in the world, whom would you want as a dinner guest?

- Would you like to be famous? In what way?

- Before making a telephone call, do you ever rehearse what you are going to say? Why?

- What would constitute a “perfect” day for you?

- When did you last sing to yourself? To someone else?

- If you were able to live to the age of 90 and retain either the mind or body of a 30-year-old for the last 60 years of your life, which would you want?

- Do you have a secret hunch about how you will die?

- Name three things you and your partner appear to have in common.

- For what in your life do you feel most grateful?

- If you could change anything about the way you were raised, what would it be?

- Take four minutes and tell your partner your life story in as much detail as possible.

- If you could wake up tomorrow having gained any one quality or ability, what would it be?

Set II

- If a crystal ball could tell you the truth about yourself, your life, the future, or anything else, what would you want to know?

- Is there something that you’ve dreamed of doing for a long time? Why haven’t you done it?

- What is the greatest accomplishment of your life?

- What do you value most in a friendship?

- What is your most treasured memory?

- What is your most terrible memory?

- If you knew that in one year you would die suddenly, would you change anything about the way you are now living? Why?

- What does friendship mean to you?

- What roles do love and affection play in your life?

- Alternate sharing something you consider a positive characteristic of your partner. Share a total of five items.

- How close and warm is your family? Do you feel your childhood was happier than most other people’s?

- How do you feel about your relationship with your mother?

Set III

- Make three true “we” statements each. For instance, “We are both in this room feeling…”

- Complete this sentence: “I wish I had someone with whom I could share…”

- If you were going to become a close friend with your partner, please share what would be important for him or her to know.

- Tell your partner what you like about them; be very honest this time, saying things that you might not say to someone you’ve just met.

- Share with your partner an embarrassing moment in your life.

- When did you last cry in front of another person? By yourself?

- Tell your partner something that you like about them already.

- What, if anything, is too serious to be joked about?

- If you were to die this evening with no opportunity to communicate with anyone, what would you most regret not having told someone? Why haven’t you told them yet?

- Your house, containing everything you own, catches fire. After saving your loved ones and pets, you have time to safely make a final dash to save any one item. What would it be? Why?

- Of all the people in your family, whose death would you find most disturbing? Why?

- Share a personal problem and ask your partner’s advice on how he or she might handle it. Also, ask your partner to reflect to you how you seem to be feeling about the problem you have chosen.

One of the pivotal aspects of this research is the psychology of self-disclosure. Self-disclosure refers to the act of revealing personal information about oneself to others. It’s a critical component of relationship building because it allows individuals to share their true selves, fostering a sense of connection and trust. The theory is supported by social penetration theory, which suggests that as relationships develop, communication moves from superficial layers to deeper, more intimate levels.

Aron’s research aligns with the concept of reciprocal vulnerability, where both parties share personal information, creating a balanced dynamic of openness and trust. This process can accelerate the feeling of closeness between individuals, as each person feels understood and accepted.

The 36 questions experiment yielded fascinating results. Many participants reported feeling a deep sense of connection and closeness with their partners, even when they were strangers at the beginning of the study. Some even formed lasting relationships, leading to the popular notion that these questions can make people fall in love.

Substantiating the research

Beyond the initial study, several other researchers have explored the impact of Aron’s questions and the principles behind them. Studies have consistently shown that structured self-disclosure exercises can enhance feelings of intimacy and connection. For instance, a study by psychologist Mandy Len Catron replicated Aron’s experiment and found similar results, further validating the effectiveness of these questions in fostering closeness.

However, it’s essential to consider the perspectives of other psychologists on Aron’s work. While many acknowledge the value of self-disclosure in building intimacy, some argue that true love and lasting connections involve more than just answering questions. Factors such as compatibility, shared values, and emotional support also play crucial roles in the development of romantic relationships.

The practical implications of Aron’s work extend beyond romantic relationships. The principles of self-disclosure and vulnerability can be applied to various contexts to enhance social connections. In educational settings, educators can use structured questions to foster a sense of belonging and empathy among students. By encouraging open dialogues and sharing experiences, teachers can create an inclusive and supportive learning environment.

Moreover, the digital age has presented new opportunities and challenges for building connections. While technology allows people to connect across distances, it can also hinder genuine interactions. Aron’s research highlights the importance of meaningful conversations and the need to balance digital communication with face-to-face interactions.

As we consider the potential of using Aron’s questions to create high-quality connections, it’s essential to acknowledge the challenges and limitations. Building meaningful relationships requires ongoing effort, empathy, and understanding. While structured questions can facilitate initial connections, maintaining and deepening those relationships involves navigating complexities and challenges over time.

In conclusion, Arthur Aron’s research on the power of structured questions to foster intimacy and connection has had a profound impact on our understanding of human relationships. By emphasizing vulnerability and self-disclosure, Aron’s work offers valuable insights into the psychology of closeness and the potential for creating meaningful bonds.

Practical Applications

The principles behind Aron’s questions have practical applications in various domains, from improving team dynamics in organizations to enhancing educational environments and fostering social connections in communities. As we navigate the complexities of modern relationships, the importance of authentic communication and empathy remains paramount.

Ultimately, Aron’s research serves as a reminder of the profound impact that meaningful conversations can have on our lives. By embracing vulnerability and taking the time to truly understand one another, we can build stronger, more fulfilling relationships that enrich our lives and contribute to our overall well-being.

The success of Catron’s essay and the widespread interest in Aron’s experiment have led to practical applications in various contexts. Educators, therapists, and relationship coaches have explored using these questions to enhance communication and foster intimacy in different settings.

For educators, the questions offer a way to encourage students to engage in meaningful dialogues, promoting empathy and understanding in the classroom. By incorporating structured self-disclosure exercises, teachers can create an inclusive and supportive learning environment where students feel valued and heard.

In therapy, the questions can serve as a tool for couples seeking to improve their communication and deepen their emotional connection. By facilitating open dialogues and encouraging vulnerability, therapists can help couples navigate challenges and strengthen their relationships.

Relationship coaches have also adopted the questions as a means of helping clients build trust and intimacy in their personal lives. By guiding individuals through the process of self-disclosure, coaches can support them in developing more fulfilling and authentic connections.

Despite the enthusiasm surrounding Catron’s essay, some critics argue that the experiment oversimplifies the complexities of love and relationships. They caution that while the questions can facilitate initial connections, true love requires ongoing effort and commitment beyond structured exercises. Love is a multifaceted emotion that involves compatibility, shared values, and emotional support, in addition to vulnerability and intimacy. Critics emphasize that while the questions can create a sense of closeness, they are not a substitute for the deeper elements that sustain long-term relationships. Others point out that the success of the experiment may be influenced by contextual factors, such as the participants’ willingness to engage fully and their existing levels of attraction. The questions alone are not a guarantee of romantic success, but rather a catalyst for exploring potential connections.

Author:

Dr Mukesh Jain is a Gold Medallist engineer in Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering from MANIT Bhopal. He obtained his MBA from the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. He obtained his Master of Public Administration from the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University along with Edward Mason Fellowship. He had the unique distinction of receiving three distinguished awards at Harvard University: The Mason Fellow award and The Lucius N. Littauer Fellow award for exemplary academic achievement, public service & potential for future leadership. He was also awarded The Raymond & Josephine Vernon award for academic distinction & significant contribution to Mason Fellowship Program. Mukesh Jain received his PhD in Strategic Management from IIT Delhi.

Mukesh Jain joined the Indian Police Service in 1989, Madhya Pradesh cadre. As an IPS officer, he held many challenging assignments including the Superintendent of Police, Raisen and Mandsaur Districts, and Inspector General of Police, Criminal Investigation Department and Additional DGP Cybercrime, Transport Commissioner Madhya Pradesh and Special DG Police.

Dr. Mukesh Jain has authored many books on Public Policy and Positive Psychology. His book, ‘Excellence in Government, is a recommended reading for many public policy courses. His book- “A Happier You: Strategies to achieve peak joy in work and life using science of Happiness”, received book of the year award in 2022. After this, two more books, first, A ‘Masterclass in the Science of Happiness’ and the other, ‘Seeds of Happiness’, have also been received very well. His book, ‘Policing in the Age of Artificial Intelligence and Metaverse’ has received an extraordinary reception from the police officers. He is a visiting faculty to many business schools and reputed training institutes. He is an expert trainer of “Lateral Thinking”, and “The Science of happiness” and has conducted more than 300 workshops on these subjects.

Leave a reply to School Of Happiness Cancel reply