In the late 1990s, two Harvard psychologists quietly changed how the world understands attention. Their experiment did not involve complex machines, brain scans, or large budgets. Instead, it involved a short video, a group of students passing basketballs, and a man in a bulky gorilla suit.

The researchers were Dr. Daniel Simons and Dr. Christopher Chabris, both deeply curious about how attention really works. At the time, psychology textbooks described attention as a kind of spotlight — whatever you point it toward becomes clear and sharp. Simons and Chabris wondered if the story was more complicated. Could it be that when we focus deeply on one thing, we actually miss other things completely?

They decided to put this question to the test.

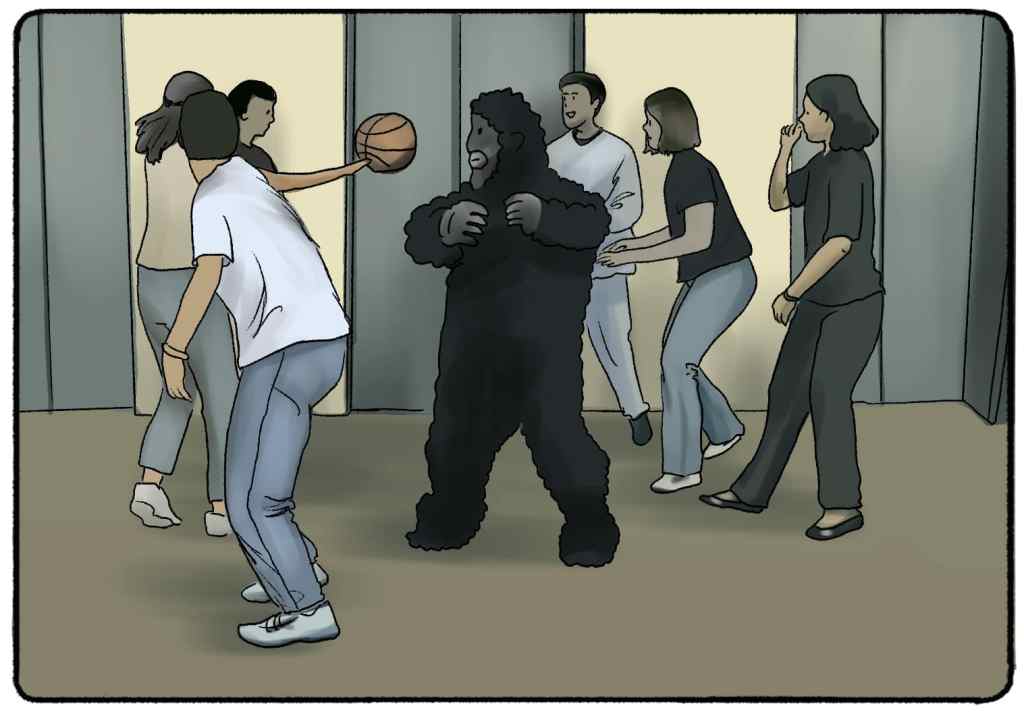

The setup was extremely simple. Volunteers were shown a video of two teams — one wearing white T-shirts, the other wearing black — passing basketballs back and forth. Participants were told to count how many passes the team in white made. It sounds easy, almost boring. But that was the point. The task forced the viewer to concentrate.

What none of the participants were told was that halfway through the video, a man dressed in a gorilla suit would walk directly into the scene. He would pound his chest, pause for a moment, and walk out. It was impossible to miss — or at least, that’s what everyone assumed.

Simons and Chabris were stunned by what happened next.

Nearly half of all viewers did not see the gorilla at all. They watched the video. They counted the passes. They finished their task. And when the researchers asked, “Did you see anything unusual?” many confidently replied, “No.”

When the video was played again, without any instructions, jaws dropped. People laughed. Some refused to believe it was the same video. They were shocked not because the gorilla was subtle — it wasn’t — but because it had walked right through their field of vision and their mind never registered it.

The Invisible Gorilla Study became famous because it revealed a truth that affects every part of life:

we notice far less than we think we do.

Simons and Chabris called this phenomenon inattentional blindness — the failure to notice something obvious because our attention is occupied elsewhere. It was a scientific confirmation of a universal human experience: when we are too focused on one thing, we become blind to everything else.

This wasn’t the first time the idea appeared in psychology. Earlier studies by Dr. Ulric Neisser, often called the “father of cognitive psychology,” showed a similar effect. In one of his experiments, participants watched people pass basketballs while a woman with an umbrella walked through. Many did not notice her. But Simons and Chabris took the idea mainstream by creating a clear, dramatic, unforgettable demonstration.

Their research went deeper. In their book The Invisible Gorilla, they explained that inattentional blindness is not a flaw — it is part of how the human brain works. Attention is limited. We cannot process everything at once. So the brain chooses, narrows, filters, and focuses on what it believes matters. This ability helps us survive, but it also causes us to miss things that feel obvious in hindsight.

“People think they notice everything important,” Simons once said, “but our intuitions deceive us. We’re often much more blind than we realize.”

The implications are enormous. In driving, for example, inattentional blindness causes accidents. A driver might look directly toward a motorcyclist or pedestrian, yet fail to see them consciously because their mind is focused on something else. In workplaces, leaders may miss early warning signs of conflict or fatigue because their attention is consumed by targets or deadlines. In relationships, we often overlook emotional signals in the people we love because our minds are busy rehearsing tasks and responsibilities.

Even in daily life, inattentional blindness shapes how we experience the world. We see not with our eyes but with our attention.

Other studies have confirmed this again and again. In one experiment, radiologists — highly trained experts — scanned lung X-rays with a hidden gorilla-size picture embedded faintly in the film. Over 80% did not notice it. Their expertise did not protect them from inattentional blindness; in fact, deep focus increased the likelihood of missing unexpected stimuli.

Another study by Yale researchers showed that even when people know to expect surprises, they still miss them if they are not the “right kind” of surprise. In short, our attention has a personality of its own: selective, unpredictable, and anything but perfect.

But The Invisible Gorilla Study also teaches something hopeful. If inattentional blindness is normal, then missing things does not make us careless or flawed. It makes us human. The real opportunity lies in what we do with this awareness.

It encourages us to pause. To broaden our attention. To look up from our screens. To listen more deeply. To stay present with the people around us. To remember that the world is always offering more than our eyes capture.

In a way, Simons and Chabris did for attention what Dove’s Sketches did for beauty — they held up a mirror to what we don’t see in ourselves.

And just like the women who didn’t realize their own beauty, most of us don’t realize our own blindness.

The experiment reminds us gently:

- We don’t see everything.

- We don’t know everything.

- And that humility should make us curious, not fearful.

It should make us better leaders, listeners, friends, and human beings.

Sometimes the most important “gorilla” in our lives is not a visual one — it is a truth, an opportunity, a warning, or a moment of love that we overlooked because we were too focused on something else.

The Invisible Gorilla teaches us this simple wisdom:

Pay attention.

Then pay attention again.

The world is always showing you more than you notice.