Mukesh Jain

Measuring happiness is a complex and multifaceted task that has intrigued philosophers, psychologists, and researchers for centuries. The pursuit of understanding and quantifying happiness has led to the development of various theories, models, and methodologies. In this exploration, we will delve into some of the key approaches to measuring happiness, acknowledging the inherent challenges and nuances associated with this subjective and elusive phenomenon.

One prominent method for assessing happiness is through subjective well-being (SWB), which encompasses an individual’s overall evaluation of their life and emotional experiences. SWB is often measured through self-reporting, where individuals are asked to reflect on their life satisfaction, positive emotions, and the absence of negative emotions. Surveys and questionnaires, such as the widely used Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) and Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS), provide researchers with quantitative data to gauge individuals’ perceived happiness.

However, relying solely on self-reports poses certain limitations. Individual perceptions of happiness can be influenced by various factors, including cultural norms, personal expectations, and social desirability biases. Additionally, people might struggle to accurately recall or express their emotional states, leading to potential inaccuracies in the data. Therefore, researchers often complement self-report measures with other objective indicators to provide a more comprehensive understanding of happiness.

One such objective measure is physiological assessments, which examine biological markers associated with happiness. Neuroscientific research has identified brain regions and neurotransmitters linked to positive emotions. Functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) and electroencephalography (EEG) enable researchers to observe brain activity in response to stimuli that elicit happiness. The release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin is also associated with pleasurable experiences, offering a biochemical perspective on happiness.

However, physiological measures have their own set of challenges. Biological responses can be influenced by various factors, including genetics, individual differences, and external environmental conditions. Furthermore, physiological indicators might not capture the entirety of the subjective experience of happiness, as emotions are complex and multifaceted phenomena that extend beyond mere neural and biochemical processes.

Another avenue for measuring happiness involves examining behavioral indicators. Observing how individuals behave in different contexts can provide valuable insights into their emotional states. For example, facial expressions, body language, and vocal tone are non-verbal cues that convey emotions. Behavioral economics explores decision-making and choices as indicators of well-being, considering factors like consumption patterns, financial decisions, and time allocation.

Nevertheless, relying solely on behavior as a measure of happiness has its limitations. People often engage in adaptive behaviors to conform to societal expectations or navigate challenging situations, creating a potential mismatch between observed behaviors and genuine emotional states. Additionally, cultural variations in expressive norms can influence the interpretation of behavioral cues, emphasizing the need for a culturally sensitive approach to happiness measurement.

Beyond individual assessments, societal well-being indicators offer a broader perspective on happiness at the collective level. Gross National Happiness (GNH), introduced by Bhutan, represents an alternative to traditional economic metrics like Gross Domestic Product (GDP). GNH considers factors such as psychological well-being, health, education, and environmental sustainability to provide a more holistic measure of a nation’s prosperity.

While societal indicators contribute to a more comprehensive understanding of happiness, they too face challenges. Determining the weighting of different components in a composite index can be subjective, and cultural variations may influence the relevance of certain factors. Additionally, aggregating individual experiences into a societal measure raises ethical questions about the prioritization of specific well-being dimensions.

As technology advances, big data and machine learning have also been employed to analyze large-scale datasets for patterns and trends related to happiness. Social media, in particular, provides a vast source of information where individuals express their thoughts, feelings, and experiences. Sentiment analysis algorithms can be applied to extract emotional tones from text, offering real-time insights into collective happiness levels.

However, relying on digital footprints for happiness measurement comes with ethical considerations. Issues such as privacy, consent, and the potential distortion of online personas highlight the need for responsible and transparent data practices. Additionally, digital expressions may not fully capture the richness and depth of human emotions, emphasizing the importance of combining technological approaches with traditional methods.

In conclusion, measuring happiness is a multifaceted endeavor that requires a combination of subjective, objective, individual, and societal perspectives. Self-report measures, physiological indicators, behavioral observations, and societal well-being indices each contribute valuable insights to our understanding of happiness, yet they all come with their own set of challenges and limitations.

A holistic approach to measuring happiness involves integrating multiple methods, recognizing the interplay between subjective experiences and external factors. Culturally sensitive assessments, ethical considerations, and an awareness of the dynamic nature of happiness contribute to the ongoing dialogue surrounding this complex and elusive phenomenon. While no single metric can encapsulate the entirety of human happiness, the interdisciplinary pursuit of understanding and measuring it enriches our collective knowledge and informs efforts to enhance well-being on both individual and societal levels.

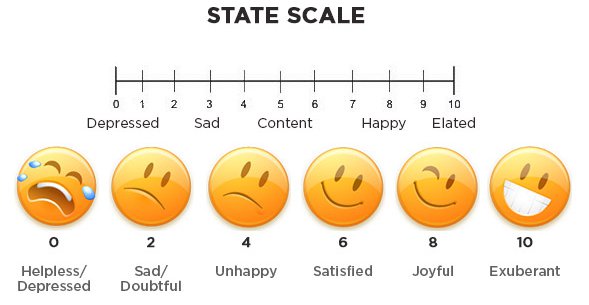

Several scales have been developed to measure happiness. For example, the subjective happiness scale (SHS) developed by Sonja Lyubomirsky is a 4-item scale of global subjective happiness. Two items of the scale ask the respondents to characterize themselves in absolute manner and in relative manner comparing themselves to the peers. The other two items offer brief descriptions of happy and unhappy people and ask the respondents the extent to which the descriptions match their own personality.

Another famous scale to measure happiness was developed by Edward Diener, a psychology professor of the University of Virginia, and author of the bestseller, ‘Happiness: Unlocking the mysteries of psychological wealth’, developed the ‘Satisfaction with life scale’ which is global cognitive assessment of life satisfaction. This scale requires a person to use a seven – item scale to agree or disagree about their life.

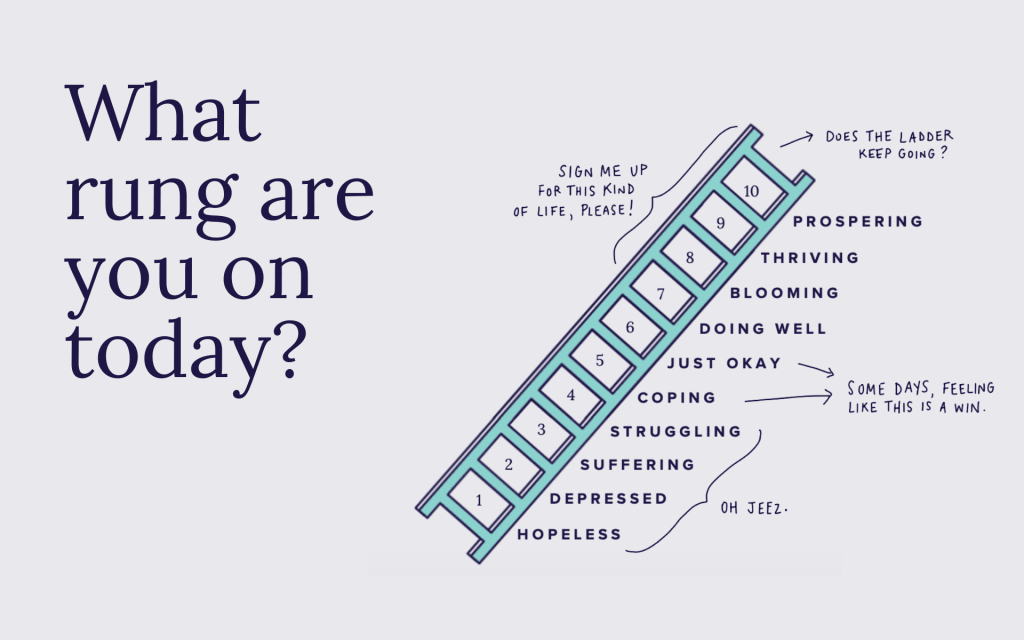

Another scale, used by the World Happiness Report, is the ‘Cantril Ladder method’ which asks the respondents to imagine a ladder with steps numbered from zero the bottom of ten at the top. If asks, suppose the top of the ladder represents the best possible life for you and the bottom … of the ladder representing the most possible life, where would the participants like to place himself presently.

In last 25 years, the field of positive psychology has generated solid empirical research into areas such as well-being, personal strengths, flow, creativity, wisdom, psychological health to teams and groups in institutions. Positive psychology, the science of flourishing, has succeeded in pulling happiness out of the domain of philosophy and anecdotes. More than 25 years of research by many positive psychologists across the world have collected enough research base enabling us to decide on the interventions and choices which lead to happiness in life.

Dr Mukesh Jain is a Gold Medallist engineer in Electronics and Telecommunication Engineering from MANIT Bhopal. He obtained his MBA from the Indian Institute of Management Ahmedabad. He obtained his Master of Public Administration from the Kennedy School of Government, Harvard University along with Edward Mason Fellowship. He had the unique distinction of receiving three distinguished awards at Harvard University: The Mason Fellow award and The Lucius N. Littauer Fellow award for exemplary academic achievement, public service & potential for future leadership. He was also awarded The Raymond & Josephine Vernon award for academic distinction & significant contribution to Mason Fellowship Program. Mukesh Jain received his PhD in Strategic Management from IIT Delhi.

Mukesh Jain joined the Indian Police Service in 1989, Madhya Pradesh cadre. As an IPS officer, he held many challenging assignments including the Superintendent of Police, Raisen and Mandsaur Districts, and Inspector General of Police, Criminal Investigation Department and Additional DGP Cybercrime, Transport Commissioner Madhya Pradesh and Special DG Police.

Dr. Mukesh Jain has authored many books on Public Policy and Positive Psychology. His book, ‘Excellence in Government, is a recommended reading for many public policy courses. His book- “A Happier You: Strategies to achieve peak joy in work and life using science of Happiness”, received book of the year award in 2022. After this, two more books, first, A ‘Masterclass in the Science of Happiness’ and the other, ‘Seeds of Happiness’, have also been received very well. He is a visiting faculty to many business schools and reputed training institutes. He is an expert trainer of “Lateral Thinking”, and “The Science of happiness” and has conducted more than 300 workshops on these subjects.